Tamsui | Taiwan

On bilingual road signs around Taiwan, almost every place name is spelled according to its pronunciation in Mandarin. Tamsui is one of the few exceptions, because it’s been the location of key interactions with the outside world. Sometimes written Danshui (which reflects the pronunciation used by most 21st-century Taiwanese people when referring to this charming rivermouth town), the Tamsui of a century-and-a-half ago was home to church-planting missionaries, diplomats from Western nations, and merchants who introduced Taiwanese tea to distant markets. Some of these expatriates lie buried in Tamsui’s foreigners cemetery, which is an historical attraction in its own right.

Originally the stomping ground of the long-disappeared Ketagalan tribe of Austronesian indigenous people, the earliest settlers from China called this place Hobe, derived from the Ketagalan toponym, which meant ‘rivermouth’. The word Hobe still appears in a few places, for instance in the name of a still-intact fortress built in 1888 at the behest of the Qing dynasty authorities then in charge of Taiwan. The fort is an excellent example of the stable door being closed after the horse had bolted. It was completed too late to make any difference during the Sino-French War and totally unsuited to the kind of modern warfare the Japanese practiced when seizing control of Taiwan in 1895.

Originally the stomping ground of the long-disappeared Ketagalan tribe of Austronesian indigenous people, the earliest settlers from China called this place Hobe, derived from the Ketagalan toponym, which meant ‘rivermouth’. The word Hobe still appears in a few places, for instance in the name of a still-intact fortress built in 1888 at the behest of the Qing dynasty authorities then in charge of Taiwan. The fort is an excellent example of the stable door being closed after the horse had bolted. It was completed too late to make any difference during the Sino-French War and totally unsuited to the kind of modern warfare the Japanese practiced when seizing control of Taiwan in 1895.

Missionaries, merchants, and Mazu

A few decades earlier, the Qing court in Beijing had been forced to open Tamsui and other ports in Taiwan and China to foreign traders under one of the notorious ‘unequal treaties’ imposed on a weak China by Western powers. In addition to tea, soon large quantities of camphor, coal, dyes, and opium were moving through Tamsui’s docks. The British established a consulate here (the consul’s residence is still standing) and the legendary Canadian Presbyterian missionary George L. Mackay (1844–1901) [a bust of whom is shown on the left] set up schools and clinics. In addition to various buildings and relics associated with the town’s first Western residents, at least one site linked with the fifty years of Japanese colonial rule deserves a bit of every traveller’s time: The Former Residence of Tada Eikichi was built in 1934 to accommodate a Japanese civil servant who served as unelected chief of Tamsui. This elegant and very Japanese-looking bungalow is no palace but its residents would have enjoyed million-dollar views of the river.

Like every Taiwanese settlement that’s bigger than a hamlet, Tamsui has temples where local people worship a range of popular, Taoist, Buddhist, and folk deities. Almost every visitor pops into Fuyou Temple on the main road and so should you. Dedicated like so many other religious sites to Mazu, the effigy here is credited with helping the Qing forces resist European invaders during the Sino-French War of 1884-85. In recognition of the goddess’s assistance, the emperor himself sent a four-character inscribed board which still holds pride of place. Roughly translated when read from right to left (as is usually the case with premodern Chinese script), it means ‘the blessings of the bright heaven’.

However, Tamsui’s most beautiful place of worship isn’t its most visited. Yinshan Temple — less than 500 m (0.3 miles) from the metro station but away from other sights — honours Dipankara, a Buddha who lived before Gautama Buddha (the historical Buddha) and was worshipped by many of the Hakka migrants reaching northern Taiwan in the early 19th century. After World War II, the temple suffered serious neglect, some of its treasures being stolen. The first renovation was botched yet the shrine’s supporters, many of them descendants of the individuals who established it in 1824, persisted, eventually winning plaudits and subsidies from the government.

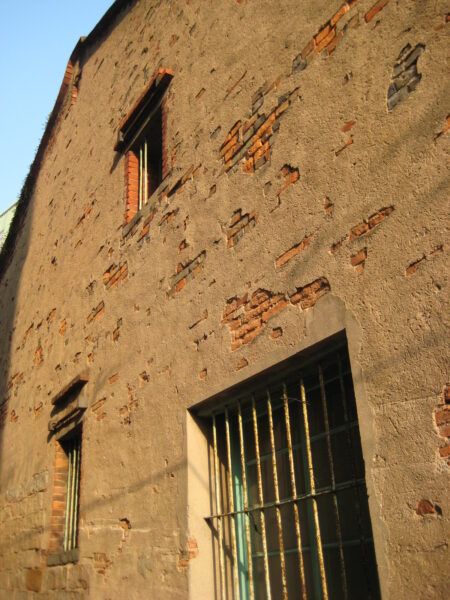

Perhaps the most memorable attraction in Tamsui is Fort San Domingo [pictured at the top of this page], an eyecatching mini-castle that’s stood here since 1646. Constructed by Dutch East India Company soldiers and imported labourers during the period when the Dutch also occupied Tainan, it’s actually a rebuild of a crude stockade erected then abandoned by the Spanish in the 1630s. Because Taiwanese people in the 17th century regarded Northern Europeans as ‘red-haired barbarians’, the fort was nicknamed Hongmao Cheng, meaning ‘castle of the red-haired folk’. In the 19th century, the building served first as a Qing barracks then as the British consul’s office. Downstairs there are cells for the detention of British citizens; under the provisions of the treaty that opened Tamsui to foreign trade, Britons were immune to local laws but could face punishment from UK authorities. Despite the British government recognising the Communist regime in Beijing as early as 1950, this consulate stayed open until 1972; diplomats based here had to avoid meeting any of Chiang Kai-shek’s ministers but could engage with local-level officials.

Fans of the performing arts may be intrigued to know that Cloud Gate Theatre, the internationally-acclaimed Taiwanese dance troupe, has its main base in Tamsui, less than a mile inland of Fort San Domingo. This striking building, paid for by donors from around the world after the troupe’s previous headquarters burned down, contains performance spaces, dressing rooms, rehearsal studios, offices, and even a space in which the dancers can meditate ahead of shows.

Across the river and up the coast

If you’re staying overnight in or near Tamsui, consider spending a few hours on the other side of the river in Bali (not to be confused with the Indonesian island, of course). From the little ferry that connects the two you’ll get good views of both Yangmingshan National Park to the east and Guanyinshan (612 m / 2,008 ft) to the south. The latter is one of several hills around Taiwan named in honour of the Buddhist goddess of mercy. Renting a bike is one way to explore Bali but it’s just about possible to walk beyond the mangrove swamps as far as Shihsanhang Museum of Archaeology, where you can learn about the iron-smelting prehistoric inhabitants of this part of Taiwan.

Before reaching the town of Jinshan, art lovers may want to detour to Ju Ming Museum, which celebrates the achievements of internationally renowned sculptor Ju Ming (1938–2023) and displays much of the art he collected in his lifetime. The spiritually minded may prefer the Dharma Drum Mountain World Center for Buddhist Education. Founded in 1989 by one of the country’s most respected monastics, the Venerable Chan Master Sheng-Yen (1930–2009), this sprawling complex welcomes casual visitors; Life of Taiwan can help arrange a more in-depth introduction if given a few weeks’ notice. Whatever your interests, our travel experts are eager to deploy their experience and connections to create an unbeatable experience for you and your travelling companions. Contact us today and get the ball rolling!