People & Languages of Taiwan

Waves of immigration have resulted in a population that’s surprisingly diverse. The bulk of citizens fall into four categories, listed below in the order in which they arrived in Taiwan.

The Indigenous People

Taiwan’s indigenous tribes have been on the island for thousands of years, but are now a tiny minority. Just one in forty Taiwanese is officially aboriginal, yet a far greater proportion – possibly half of the population – has some indigenous heritage. Tsai Ing-wen, Taiwan’s president from 2016 to 2024, has partial Paiwan ancestry from her grandmother.

All of Taiwan’s native tribes – officially there are 16, with a few more groups campaigning for recognition – are Austronesian, and many experts believe Taiwan is where the Austronesian branch of mankind started out. Each tribe has its own language, yet many young aborigines can’t speak more than a few words in their ancestral tongue.

Well into the 20th century, many Taiwanese of Han Chinese origin (be they Hoklo or Hakka) regarded the island’s indigenous people as savages, and it’s true that as recently as the 1930s some groups hadn’t given up their old head-hunting ways. The Japanese colonial authorities tried to stamp out certain practices they regarded as backward, such as the tattooing of women’s faces.

Indigenous clans in the mountains lived by hunting and gathering, and hunting remains a popular pastime among indigenous communities in the highlands. The lowland aborigines (also called Pingpu tribes) farmed and raised livestock. Nowadays, native people can be found doing all kinds of jobs. They’re especially well-represented in sport and music; many become professional soldiers or police officers.

Indigenous villages are transformed during celebrations such as the Amis Harvest Festival held in several villages in the East Rift Valley. Residents of all ages don traditional costumes and take part in outdoor dances; beautiful polyphonic melodies are sung; and young men engage in contests to show off their strength and skill.

Unlike the majority of their Han compatriots, most Taiwanese aborigines are Christian.

Aboriginal Tribes

Officially, 588,000 of Taiwan’s 23.4 million people are indigenous. In order of size, the 16 tribes recognised by the government are:

- Amis (Pangcah) – almost 219,000 adults and children, living mainly in Hualien and Taitung.

- Paiwan – close to 106,000, in the counties of Pingtung and Taitung.

- Atayal – more than 94,000, over a large area of highlands including parts of New Taipei, Hualien, Hsinchu and Nantou.

- Bunun – around 61,000, in the mountainous parts of Nantou, Kaohsiung, and East Taiwan.

- Truku – over 33,000, in and around Taroko Gorge.

- Puyuma – 15,000, mostly in Taitung.

- Rukai (Drekay) – nearly 14,000, in Kaohsiung’s Maolin District and parts of Pingtung and Taitung.

- Seediq – 11,000, in the high-altitude north and east of Nantou County (where they led a major uprising against Japanese rule in 1930) and in a few parts of Hualien County.

- Tsou – fewer than 7,000, around Alishan.

- Saisiyat – fewer than 7,000, in Hsinchu and Miaoli.

- Tao – 4,800, mostly on Orchid Island; also known as the Dawu or Yami people.

- Kavalan – 1,500, in Hualien and Yilan.

- Thao – fewer than 900, around Sun Moon Lake.

- Sakizaya – just over 1,000, living among Amis people in Hualien.

- Kanakanavu – fewer than 500, living in inland Kaohsiung.

- Hlaalua – fewer than 500, living near the Kanakanavu in Kaohsiung.

Cultural differences between the tribes include facial tattooing (customary among the Atayal, Paiwan, Puyuma, Rukai, Saisiyat, Seediq, and Truku) and hand tattooing (confined to the Paiwan and Rukai tribes). The last aboriginal woman with traditional face tattoos died in 2022 at the age of 106; in recent years, however, a handful of young people have had their faces tattooed. All of the tribes have strong musical traditions (one reason why indigenous people are especially prominent in Taiwan’s pop music and entertainment industries) and distinctive costumes. Traditional clothing is often worn during festivals or on Sundays when attending church.

Taiwan’s tribes are struggling to preserve their cultures because of the influence of mass media (although some TV and radio shows are broadcast in indigenous languages), an education system which until recently stressed Mandarin at the expense of every other language, and migration. The majority of young indigenous people leave their home villages to work or attend school in a city, although it’s common for them to return and enthusiastically participate in tribal festivals.

Compared to other Taiwanese, the average native person isn’t well off. Not many graduate from college, and their life expectancy is shorter. To improve their lot, various government programs help indigenous people get scholarships and jobs. If you’re interested in learning more about Taiwan’s original inhabitants, contact us today to begin planning a customised private guided tour of Taiwan.

The Hoklo people

About three quarters of Taiwan’s population think of themselves as ‘ordinary Taiwanese’, meaning they’re neither indigenous, Hakka, nor mainlander. The ancestors of Taiwan’s Hoklo population migrated to the island from Fujian – the mainland Chinese province nearest Taiwan – sometime between the early 1600s and the Japanese takeover in 1895. Most of them speak Taiwanese (a language very similar to Minnanhua in Fujian), and many reject the idea that Taiwan is part of China, even though they recognise they are of Han Chinese descent.

The overwhelming majority of people in Chiayi, Tainan, and Pingtung are Hoklo. In East Taiwan, because there are large Hakka, indigenous, and mainlander minorities, Hoklo people account for less than half the population. Despite their numbers, it wasn’t until 2000 that a Hoklo politician held the presidency, when Chen Shui-bian (b1950) took the top job.

The Hakka people

Hakka people, who are found throughout the Chinese mainland and southeast Asia, began settling in Taiwan in the early 18th century. This Han Chinese ethnic group has its own language and customs, preserved despite numerous scatterings and migrations over the past 1,600 years. Particular deities in the Chinese folk pantheon are regarded as Hakka gods. Unlike Hoklo families, Hakka parents never bound the feet of their daughters.

Taiwan’s three million Hakka people are concentrated in the northwest and in a few towns in the far south, because by the time they arrived on the island, the best farming land had already been taken by Hoklo settlers. Consequently, the Hakkas had to make do with marginal and foothill areas. Once treated as outcasts, in recent generations Hakka people have been respected for educational success and hard work. Meinong, a exceptionally picturesque town in Kaohsiung, is said to have produced more PhD holders relative to its population than anywhere else in Taiwan. Lee Teng-hui (1923-2020), a Hakka who has a PhD from Cornell University, became Taiwan’s first native-born president in 1988.

Mainland Chinese and their descendants

Between 10 percent and 15 percent of the ROC population is considered to be ‘mainlanders’. This includes a great many people born in Taiwan, as in traditional Chinese thinking a person’s ancestry comes from his or her father. Accordingly, many ROC citizens who have a Taiwanese mother and who’ve never visited the People’s Republic of China are thought of as ‘mainlanders’.

When the KMT retreated to Taiwan in 1949, 600,000 soldiers and up to a million civilians moved with them. This latter group was fantastically diverse. Among them were not only government officials, but also a good many scholars, Buddhist monks, Muslims, many of Shanghai’s businessmen, and even Christian missionaries originally from Western countries. Many of these refugees settled in Taipei, which is why the city offers a fabulous range of Chinese cuisines.

Military men were barred from marrying while in the army, so many took much younger Hoklo wives when they retired after the age of 40, even if they’d had a family on the Chinese mainland. It isn’t unusual to meet fortysomethings in Taiwan whose parents are very different in age, and who have seventysomething half-brothers and half-sisters in the People’s Republic of China.

Perhaps Taiwan’s most prominent mainlander is Ma Ying-jeou (b1950). Born in Hong Kong and raised in Taipei, he served as Taiwan’s president between 2008 and 2016. The current mayor of the capital, Chiang Wan-an (b1978) is another Taiwan-born ‘mainlander’– and a great-grandson of former President Chiang Kai-shek to boot.

Taiwan’s languages

Taiwan’s languages

Most people in Taiwan speak more than one language, but often English isn’t one of them. The official language is Mandarin Chinese, and it’s more or less the same as the official language of the People’s Republic of China. That said, each part of China has a regional accent, plus different expressions, so Mandarin speakers are usually able to distinguish mainlanders from Taiwanese by the way they talk.

With varying degrees of fluency, most of Taiwan’s people speak what they call Taiwanese, but what language scientists call Holo, Hokkienese, or Minnanhua. Between the 1950s and the 1980s, Taiwan’s education system stressed Mandarin at the expense of Taiwanese; students who spoke Taiwanese in the classroom risked punishment. Realising that Mandarin proficiency is needed for any decent career, many parents decided to speak Mandarin rather than Taiwanese to their children. As a result, while almost everyone born in Taiwan 65 or more years ago speaks fluent Taiwanese, many of those born in last few decades don’t speak the language well. What’s more, the ability to speak Taiwanese is no longer a clear indicator whether a person is Hoklo or not. For similar reasons, few young people are proficient in Hakka, even if both parents are Hakka. That said, young people in the cities are far more likely to speak English than older people and country folk. Among nonagenarian Taiwanese, many can speak Japanese well because they attended school during the Japanese occupation.

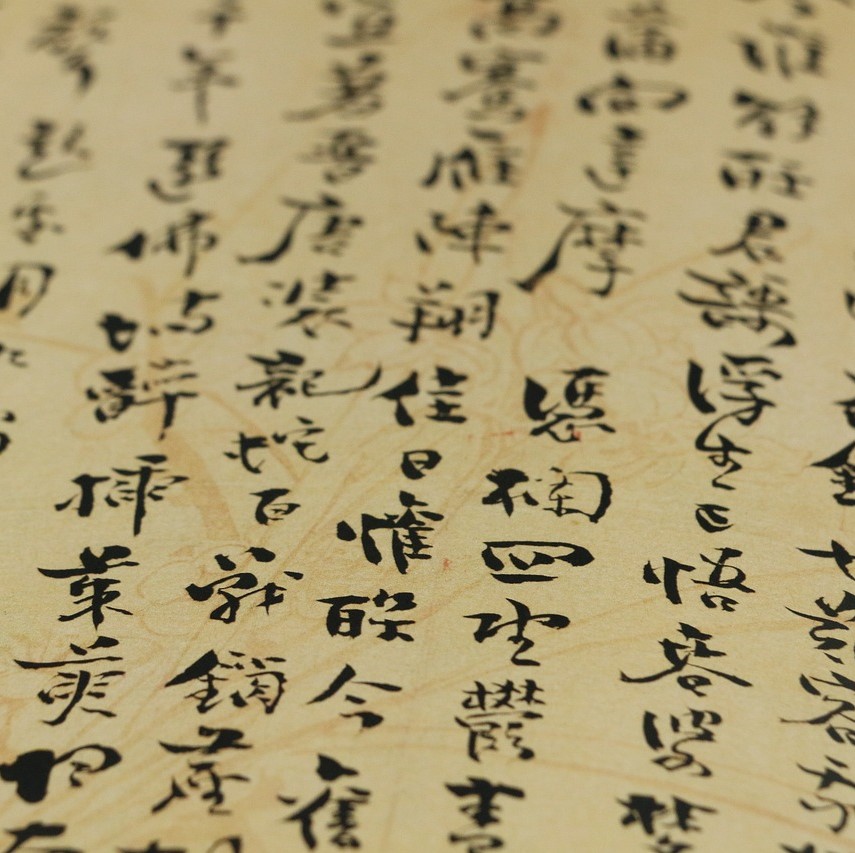

Like other Chinese languages (such as Mandarin, Hakka and Cantonese), Taiwanese is written using Chinese characters. In Taiwan, traditional ‘long form’ characters are still used, unlike the simplified ‘short form’ characters taught in schools in the People’s Republic of China and Singapore. Long-form characters are more difficult to learn but, many feel, better preserve the beauty of China’s ancient system of writing.

The indigenous languages spoken by Austronesian minority are very different to Chinese. According to some scholars, Austronesian languages can be divided into ten branches, nine of which exist only in Taiwan; all Austronesian languages spoken outside Taiwan (including the language of Orchid Island’s Tao people) belong to the Malayo-Polynesian branch, a family of 1,200-plus languages spoken by over 350 million people. Sadly, several of Taiwan’s remarkable indigenous tongues are on the verge of extinction.